Double Diabetes: Supporting Patients Through the Diagnostic Overlap

If you’ve never heard the term “double diabetes” before, don’t be alarmed. It’s not an official diagnosis, and you likely won’t find it in a medical textbook. However, it’s a term that’s gaining traction to describe a growing population of adults whose diabetes doesn’t fit neatly into the diagnostic criteria for either type 1 or type 2.

Sometimes referred to as “hybrid diabetes,” “type 1.5,” or “LADA” (Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults), recent research suggests that the distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes is less clear-cut than previously thought. In some cases, features of both types can coexist.

While it may seem like a matter of semantics, accurate classification is important. It helps guide treatment decisions and offers insight into long-term risks, disease progression, and underlying pathophysiology.

So, what exactly is double diabetes—and how does it develop? Let’s take a look at the current research and clinical recommendations.

Classifying Diabetes

The World Health Organization defines diabetes as a “chronic metabolic disease characterized by elevated blood glucose,” which, over time, can lead to serious macrovascular and microvascular complications.

Initial clinical observations in the 1970’s led to the classification of diabetes mellitus into two distinct forms—Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is typically characterized by autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing beta cells, while type 2 diabetes is defined by insulin resistance and is often associated with metabolic syndrome. Type 1 is usually diagnosed by evaluating the presence of diabetes-related autoantibodies. In contrast, type 2 is diagnosed based on the presence of hyperglycemia and evidence of relative insulin deficiency.

Since then, several additional forms of diabetes have been identified, including—but not limited to—gestational diabetes, pancreatogenic diabetes, post-transplantation, and monogenic diabetes, among others.

Double Diabetes: A New Term on the Block

The first use of the term “double diabetes” appeared in a 1991 article by Teupe et al., which observed that individuals living with type 1 who also had a family history of type 2 were more likely to have higher body weights and require larger insulin doses compared to those without such a family history. Based on these findings, the authors proposed the term to acknowledge the correlation between type 1, insulin needs, and a family history of type 2.

The term has since evolved to describe those with a diagnosis of T1D who also have a family history of type 2, are overweight or obese, and display signs of metabolic syndrome and/or insulin resistance.

The growing use of the term raises the question: Are we seeing more individuals with type 1 who exhibit coexisting features of type 2, or more cases of type 2 with an underlying autoimmune component? Others suggest that the two types of diabetes may actually exist along a continuum.

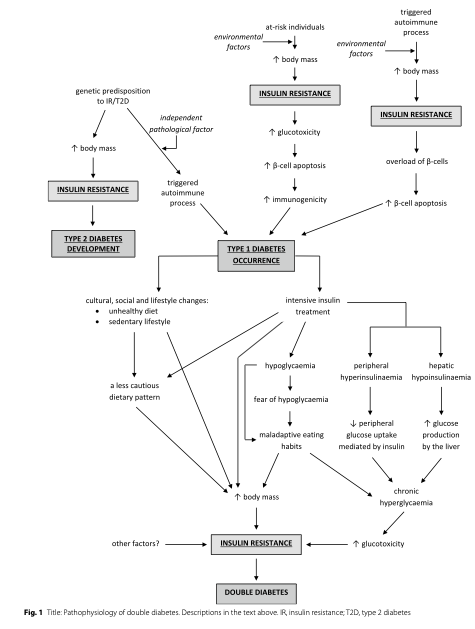

What Leads to Double Diabetes?

This is where things become less clear—it’s not entirely understood how double diabetes develops. It presents something of a “chicken or egg” dilemma:

- Did insulin resistance emerge as a result of lifestyle or weight changes in someone already living with type 1?

- Or did a person with existing insulin resistance or genetic risk for type 2 diabetes go on to develop autoimmunity, leading to type 1?

- Or, going a step further—could the presence of insulin resistance itself somehow contribute to the development of type 1 diabetes?

An Obesogenic Environment

In the first scenario, individuals living with type 1 are just as much at risk for developing overweight or obesity as anyone else in our obesogenic environment. In fact, they may be even more susceptible, as insulin therapy is often associated with weight gain.

A Genetic Predisposition

In the second scenario, individuals with type 1 may also carry a genetic predisposition to insulin resistance, particularly if they have a family history of type 2. In this case, the autoimmune process develops independently but coincidentally in someone already genetically predisposed to metabolic dysfunction.

The Accelerator Hypothesis

In contrast, the accelerator hypothesis suggests that obesity-driven insulin resistance in at-risk individuals leads to glucotoxicity, which can accelerate beta-cell death. This insulin resistance triggers an immune response, potentially leading to the production of autoantibodies, as seen in type 1 diabetes. It’s important to note that this proposed mechanism remains a theory and is still being researched.

For a more nuanced view, see the figure below illustrating the possible pathophysiology of double diabetes, as depicted by Bielka et al.

What Are the Signs of Double Diabetes?

Currently, the assessment of double diabetes is largely based on insulin needs. Dr. Thomas Haak of the Diabetes Center in Bad Mergentheim, Germany, notes that the first sign of insulin resistance in individuals with type 1 is an increased insulin requirement—typically exceeding 100 units per day.

Other contributing factors include clinical parameters such as body adiposity, waist circumference, features of metabolic syndrome—particularly elevated triglycerides and hypertension—as well as a family history of type 2 diabetes.

Researchers in more controlled settings are using advanced metrics such as estimated glucose disposal rate (eGDR), lipid accumulation product (LAP), triglyceride-glucose index (TyG index), and triglyceride-glucose waist-to-height ratio (TyG-WHtR), among others.

How Common is a Double Diabetes?

In short, double diabetes is becoming increasingly common. By some estimates, up to 1 in 4 people with type 1 also exhibit characteristics or symptoms of metabolic syndrome—typically associated with type 2 diabetes. This trend is closely linked to rising rates of obesity, particularly visceral adiposity.

Why This Deserves Our Attention

If you’ve made it this far into the article, you might be wondering—why does any of this matter? Isn’t it just an issue of labels? I would argue that having a clear understanding of the underlying pathophysiology and mechanisms of action opens the door to better clinical treatment strategies and more effective treatment.

Medication access is one key example. Very few medications are approved for use in type 1, whereas there are hundreds of drugs on the market specifically targeting insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. A more accurate classification could potentially broaden treatment options for individuals with overlapping features of both types.

Individuals with double diabetes are at higher risk for cardiovascular complications due to overlapping risk factors, like dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.

It’s also importance to note that people with double diabetes may feel confused or underserved, especially if they don’t fit neatly into the “type 1” or “type 2” category.

Key Takeaways

Double diabetes is an emerging term used to describe individuals who exhibit characteristics of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. While it is not an official diagnosis, the concept is gaining traction as more people present with overlapping clinical features.

Recognizing double diabetes carries important clinical implications. It can lead to more accurate classification, inform personalized treatment strategies, and help reduce long-term risks—particularly those related to cardiovascular health.

As our understanding of diabetes continues to evolve, so too must our clinical approach—because it’s not just about the label, but about how that label shapes care.

- Bielka W, Przezak A, Molęda P, Pius-Sadowska E, Machaliński B. Double diabetes—when type 1 diabetes meets type 2 diabetes: definition, pathogenesis and recognition. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):62. Published 2024 Feb 10. doi:10.1186/s12933-024-02145-x

- Brown AE, Walker M. Genetics of Insulin Resistance and the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(8):75. doi:10.1007/s11886-016-0755-4

- Chaudhary RK, Ali O, Kumar A, Kumar A, Pervez A. Double diabetes: a converging metabolic and autoimmune disorder redefining the classification and management of diabetes. Cureus. March 2025. doi:10.7759/cureus.80495

- Cleland SJ. Cardiovascular risk in double diabetes mellitus–when two worlds collide. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012 Apr 10;8(8):476-85. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.47. PMID: 22488644.

- Double diabetes: the silent threat hiding in type 1 patients. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/double-diabetes-silent-threat-hiding-type-1-patients-2025a10005hy. Accessed March 28, 2025.

- Khawandanah J. Double or hybrid diabetes: A systematic review on disease prevalence, characteristics and risk factors. Nutr Diabetes. 2019;9(1):33. Published 2019 Nov 4. doi:10.1038/s41387-019-0101-1

- Lakhtakia R. The history of diabetes mellitus. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13(3):368-370. doi:10.12816/0003257

- Merger SR, Kerner W, Stadler M, Zeyfang A, Jehle P, Müller-Korbsch M, et al. Prevalence and comorbidities of double diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;1(119):48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.06.003.

- Nathan D, Genuth S, Lachin J, Cleary P, Crofford O, Davis M, et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):977–986. doi:10.1056/NEJM199309303291401

- Redondo MJ, Hagopian WA, Oram R, et al. The clinical consequences of heterogeneity within and between different diabetes types. Diabetologia. 2020;63(10):2040-2048. doi:10.1007/s00125-020-05211-7

- Russell-Jones D, Khan R. Insulin-associated weight gain in diabetes–causes, effects and coping strategies. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007 Nov;9(6):799-812. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00686.x. PMID: 17924864.

You May Also Like

Mitigating Therapeutic Inertia of GLP-1 Use in T2D

August 27, 2024

Your Guide to Diabetes Supplies: Glucometers

June 4, 2023