Cortisol and Weight Gain: How Stress Affects Your Body

Cortisol has become a prominent topic in discussions about weight loss. Often referred to as the “fight or flight” hormone, it is closely associated with stress. Recently, many health and wellness influencers have suggested that elevated cortisol may be responsible for unexplained weight gain or the body’s resistance to weight loss. But is this accurate? Are abnormally high cortisol levels truly contributing to the obesity epidemic? Let’s take a look at what the science says.

What is Cortisol?

Cortisol is a steroid hormone produced by the adrenal glands, located on top of the kidneys. It is often referred to as the “stress hormone” because its levels increase in response to physical or emotional stress.

However, cortisol is essential for many other functions in the body, including:

- Regulating Metabolism. Cortisol helps manage how the body uses carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, ensuring a balanced energy supply. It promotes gluconeogenesis (the production of glucose) in the liver and affects how fats are stored in the body.

- Stress Response. During stressful situations, cortisol works with adrenaline to create the “fight or flight” response, increasing energy availability, alertness, and cardiovascular function. It temporarily raises blood sugar levels and helps the body access stored energy quickly.

- Immune System Regulation. Cortisol has anti-inflammatory properties, meaning it can suppress the immune response when necessary. This is why corticosteroid medications are often used to reduce inflammation in conditions like asthma, allergies, and autoimmune diseases.

Additionally, cortisol helps in controlling blood pressure through blood vessel response, regulating the nervous system, maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, and regulating the circadian rhythm. Clearly, cortisol is a vital and impactful hormone.

What is a "Normal" Cortisol Level?

A “normal” cortisol level from a blood sample taken at 8 a.m. typically ranges between 5 and 25 mcg/dL (140-690 nmol/L), though this can vary based on the time of day and clinical circumstances.

Cortisol levels naturally fluctuate throughout the day, peaking in the morning and dropping to their lowest in the evening. Factors that influence cortisol levels include time of day, stress, medications, health conditions, and sleep patterns.

If cortisol levels are abnormally high or low, further testing and evaluation may be required to determine the underlying cause.

What Causes Clinically HIGH Cortisol?

Clinical hypercortisolism refers to a condition characterized by an excessive amount of cortisol in the body. Hypercortisolism is most commonly associated with Cushing’s syndrome, which results from prolonged exposure to high levels of cortisol, but can also occur due to other factors, including:

- Cushing’s disease. A specific form of Cushing’s syndrome, caused by a pituitary adenoma (benign tumor) that secretes excess adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), stimulating the adrenal glands to overproduce cortisol.

- Adrenal adenoma. Tumors in the adrenal glands themselves can cause overproduction of cortisol.

- Ectopic ACTH production. Some non-pituitary tumors, such as those in the lungs, can produce ACTH, leading to excessive cortisol production.

- Steroids. Prolonged use of corticosteroid medications (e.g., prednisone) for conditions like asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, or autoimmune diseases can lead to hypercortisolism.

- Extreme and Prolonged Stress. Recent research suggests that extreme, prolonged stress can raise cortisol levels up to ninefold, though not necessarily to the levels seen in true clinical hypercortisolism.

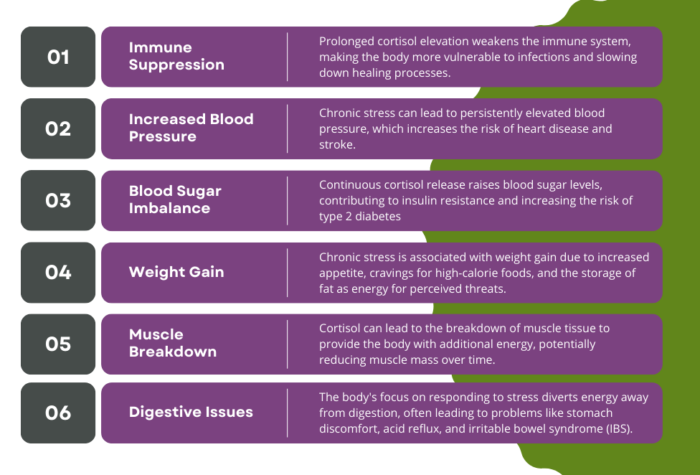

Symptoms of clinical hypercortisolism include weight gain, particularly around the abdomen and face (known as “moon face”), muscle weakness, high blood pressure, elevated blood glucose, osteoporosis, increased susceptibility to infections, and mood changes such as irritability or depression.

Acute Stress Response

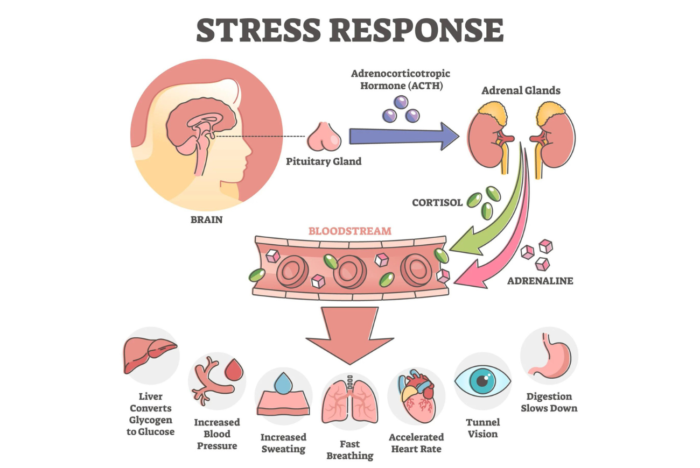

In the acute stress response, cortisol plays a crucial role in helping the body manage stress, though it is activated slightly later than the immediate effects of adrenaline.

When a stressor is perceived, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), signaling the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). This, in turn, prompts the adrenal glands to release cortisol.

Cortisol works alongside adrenaline and noradrenaline to sustain the stress response by increasing blood sugar levels, ensuring the body has adequate energy to respond to the stressor. It also suppresses non-essential functions, such as the immune response, to prevent excessive inflammation.

Cortisol breaks down fats and proteins to further increase energy availability, which can result in an increased metabolic rate and, in some cases, weight loss.

Once the stressor is removed, cortisol levels gradually return to normal, and the parasympathetic nervous system helps calm the body, restore energy, and bring systems back to baseline.

Chronic Stress Response

The body behaves quite differently during the chronic stress response. Unlike the acute response, which is short-term and meant to address immediate threats, chronic stress occurs when stressors persist over time without adequate recovery. This leads to sustained activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and continued release of cortisol and other stress hormones.

Does High Cortisol Cause Weight Gain?

In short, the answer is no—high cortisol does not directly cause weight gain. Instead, elevated cortisol increases appetite, leading to greater food intake, which in turn results in increased body fat.

A 2013 study investigated the relationship between cortisol, stress, obesity, and metabolic syndrome by evaluating 369 overweight and obese individuals and 60 healthy volunteers. Cortisol levels and metabolic parameters, such as BMI, blood pressure, and insulin resistance, were measured, and participants completed the Perceived Stress Scale.

While salivary cortisol showed some association with BMI, waist circumference, and blood pressure, there was no strong correlation between cortisol and obesity or metabolic syndrome.

In a 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis of over twenty-six studies, no association was found between basal cortisol levels and metabolic syndrome, including overweight or obesity. The results of the random-effects meta-analysis showed no significant difference in basal cortisol levels between subjects with and without metabolic syndrome.

A 2021 study examined cortisol excretion in over 1,200 patients with morbid obesity and its effects on glucose metabolism, a marker of metabolic health. While individuals with higher cortisol levels tended to be younger and more obese, they unexpectedly had lower cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood sugar. Despite their higher levels of obesity, these patients exhibited a more favorable metabolic profile.

Key Takeaways

Overall, the evidence suggests that elevated systemic cortisol is not strongly linked to obesity or metabolic syndrome. Instead, chronic and persistent stress is more likely to drive our appetite for highly palatable, dopamine-inducing foods.

Therefore, the solution may lie less in clinically assessing cortisol levels and more in adopting a holistic approach to improving work-life balance, identifying sources of stress, and developing healthy coping mechanisms.

- Cay M, Ucar C, Senol D, et al. Effect of increase in cortisol level due to stress in healthy young individuals on dynamic and static balance scores. North Clin Istanb. 2018;5(4):295-301. Published 2018 May 29. doi:10.14744/nci.2017.42103

- Abraham SB, Rubino D, Sinaii N, Ramsey S, Nieman LK. Cortisol, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study of obese subjects and review of the literature. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(1):E105-E117. doi:10.1002/oby.20083

- Garcez A, Leite HM, Weiderpass E, et al. Basal cortisol levels and metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;95:50-62. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.023

- Brix JM, Tura A, Herz CT, et al. The association of cortisol excretion with weight and metabolic parameters in nondiabetic patients with morbid obesity. Obesity Facts. 2021;14(5):510-519. doi:10.1159/000517766

You May Also Like

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Food and Nutrition Conference and Expo 2013

March 15, 2014

Remission vs Reversal

September 6, 2022