Ketogenic vs Mediterranean: A Dietary Face-Off

“What should I eat now?” is by far the most common question I hear from the newly diagnosed. The answer is both simple—and complex. Eating for good glucose management can vary greatly. Age, gender, baseline metabolism, taste preference, and even elements of nutrigenomics shape how our bodies respond to food.

The two most commonly adopted eating patterns for improved glycemic control is a variation of the Ketogenic diet and the well-known Mediterranean diet.

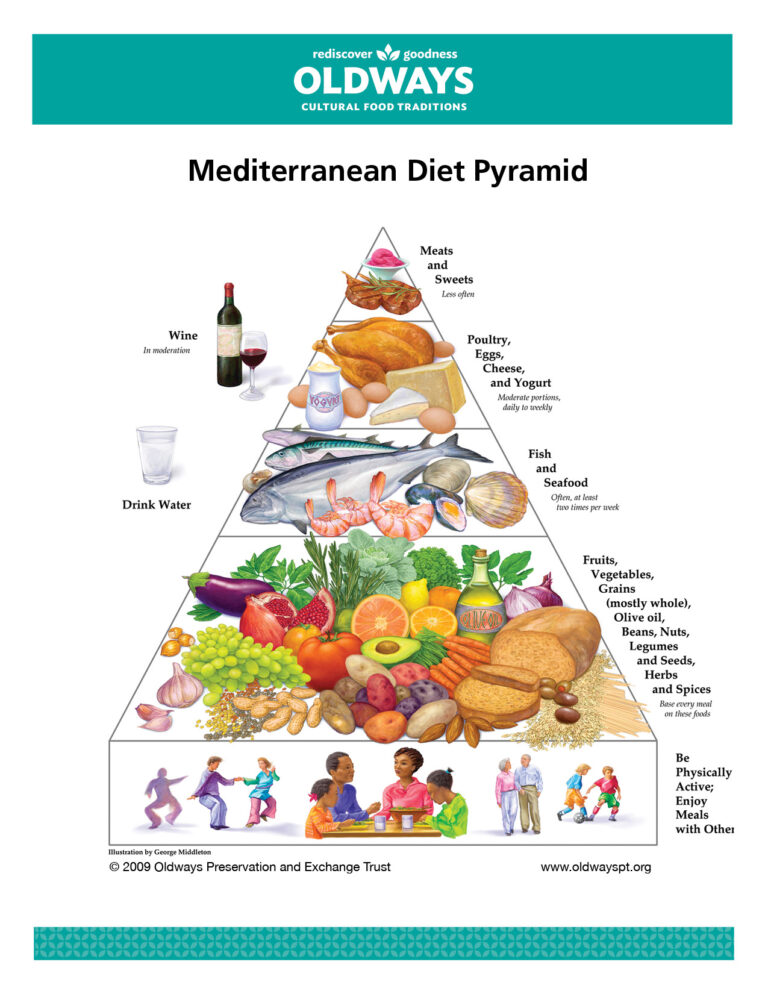

The Mediterranean Diet

Largely plant based, the “Medi diet” promotes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, beans, nuts, legumes, olive oil and herbs. Fish, seafood, poultry, eggs, cheese and yogurt are consumed a few times per week, and red meat—only on occasion. Sweets are kept to a minimum. Red wine may be enjoyed in moderation.

In the general population, the Medi diet is consistently ranked as the “top diet” on a number of factors—family friendly, budget conscious, environmentally sustainable, and supportive of good heart health.

The Medi diet also includes elements of physical activity, social connections and emotional well being. It can be interpreted as a bit of an homage to Mediterranean culture and lifestyle.

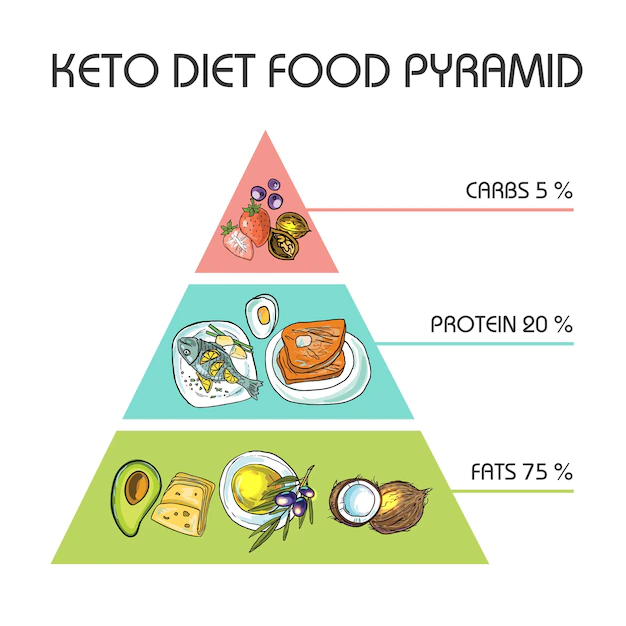

The Ketogenic Diet

In contrast, the Ketogenic diet – or “Keto diet” – promotes a high fat, moderate protein, and low carbohydrate eating pattern. While the actual percentages may vary, most aim for roughly 70% of calories from fat, 20% from protein, and less than 10% from carbohydrate. Carbohydrates should be limited to less than 30-50 grams per day. Advocates of the diet tout its ability to allow the body to enter into ketosis (fat burning) without calorie restriction.

Core foods include meat (steak, pork, ham, sausage, etc), fatty fish, eggs, butter and creams, nuts and seeds, healthy oils, avocados, herbs/spices and low carbohydrate vegetables (greens, onions, peppers, etc.).

Foods to avoid include all grains and starches (bread, rice, pasta, etc.), fruit, beans or legumes, sugar-based condiments (barbecue sauce, honey mustard, teriyaki sauce, ketchup, etc.), sweets, and alcohol.

The Keto diet is rapidly growing in popularity, with demand for Keto food products estimated to reach $14.5 billion by 2031.

Interventional Research

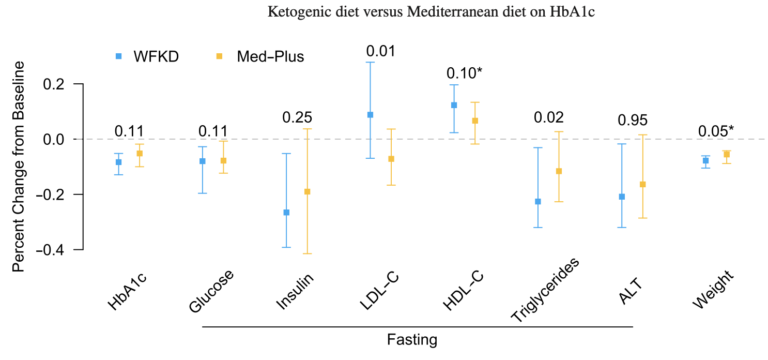

A recent randomized crossover trial out of Stanford School of Medicine compared the effects of both diets on a variety of clinical outcomes, specifically A1c, fasting glucose, and weight in individuals with T2 diabetes.

Roughly 30 study participants were randomized into two groups to follow either the Keto or Medi diet for 12 weeks, followed by another 12 weeks on the alternate diet. Health makers were assessed at baseline, 12, 24 and 36 weeks. Participants were enrolled in a meal delivery service for the first 4 weeks of each diet to ensure adherence.

Study Findings

The table below nicely summarizes key findings. The Y-axis (vertical scale) marks percentage change from baseline, indicated by the dotted line. The X-axis lists the different clinical markers. Keto is represented in blue. Medi in yellow. The square indicates the median change, with tails on either side to indicate range. With the exception of HLD, the greater the decrease from baseline—the better.

Hemoglobin A1c

A1c improved for participants on both diets. There was no significant difference between the Keto and Medi diets.

Glucose

While average glucose had a greater decrease for participants on the Keto diet, the difference is not considered “statistically significant”. Both diets improved time in range, or time spent between 70-180 mg/dL, with a slightly greater effect in the Keto diet. Again, not significantly different.

Weight

Keto diet participants did seem to lose weight a little faster, but by the end of the 24 weeks, the difference in weight loss between Keto and Medi was less than 1 kg (or 2.2 lbs). By the 36 week mark, the average difference in weight between the two groups was less than a pound.

Diet Adherence

Surprisingly, self-report adherence was similar for both diets during the food-delivery period AND the self-provided period. However, the 36 week follow-up showed that participants’ dietary patterns were more similar to the Medi diet, suggesting greater ease of long term sustainability.

So, Which Diet is Best?

Honestly, A1c can likely be reduced on any diet that restricts added sugars and refined carbohydrates (chips, cookies, crackers, pastries, breakfast cereals, etc.). Omitting fruit, legumes, and whole grains, as indicated in the Keto diet, may not be necessary to achieve good glycemic control. The key is finding an eating pattern that is effective, sustainable, and most importantly—enjoyable.

Gardner CD, Landry MJ, Perelman D, et al. Effect of a ketogenic diet versus Mediterranean diet on glycated hemoglobin in individuals with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: The interventional Keto-Med randomized crossover trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2022;116(3):640-652. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqac154

You May Also Like

Protein and Weight Loss: What’s the Big Deal?

June 18, 2024

Non-Nutritive “Artificial” Sweeteners and Weight Loss

June 4, 2024