Nutrition Strategies for Managing Postprandial Glucose

Managing blood sugars after meals can be tough. The rise is often steep and unexpected, leaving individuals scrambling to intervene—more rapid-acting insulin, a brisk walk, a liter of water—sometimes even a call to the doctor’s office. Overcorrection of hyperglycemia often results in subsequent lows, making for an unwanted game of blood sugar ping-pong.

But it doesn’t have to be this way—at least not every time. With some evidence-based nutrition strategies, steady blood sugars after meals are achievable. Fewer post-meal glucose elevations means a lower A1c, decreased risk of cardiovascular complications, and overall less blood sugar-related stress and anxiety.

Gary Scheiner, MS, CDCES and Mary Lou Perry, MS, RD, CDCES recently discussed issues surrounding postprandial glycemic control in their presentation Here’s Looking at You, Postprandial! Strategies for Managing Postmeal Glucose Levels, hosted by LifeScan Diabetes Institute. This post highlights some of their nutrition therapy recommendations.

Resistant Starch

Resistant starch is a type of carbohydrate that is not well digested in the gastrointestinal tract. Instead, it ferments in the large intestines and feeds beneficial gut bacteria. While it occurs naturally in many foods, it’s often lost through the cooking process. Some resistant starch can be regained by cooking then cooling—like rice used in sushi, a summer potato salad, or overnight oats.

A recent study in Nutrition & Diabetes showed that blood sugars following a meal of reheated rice (rice that had been previously cooked, then cooled) were much lower when compared to freshly cooked rice–even when the amount of carbohydrates were identical.

Increasing the amount of resistant starch in a meal can be an effective strategy without cutting back on total carbs.

Adding Vinegar

There is some evidence to suggest that the acidity of vinegar may benefit post-meal blood sugars. A 2017 meta-analysis in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice showed that vinegar consumption reduced postprandial glucose and while increasing insulin response. Although the type and quantity of vinegar varied between studies, adding as little as a ¼ teaspoon of vinegar to a meal may yield some benefit.

Nutrient Preload

Nutrient preloading involves consuming of a small amount of protein or fat before a meal to stimulate the release of peptides (GLP-1, GIP, and CCK) in the gut, which help slow gastric emptying and encourage insulin secretion.

A 2022 systematic review plus meta-analysis in Nutrition Research examined preloading with 15-50 grams of whey protein prior to eating a meal. Blood sugars were much lower following the meal that included preloading. Endogenous insulin production was found to have increased, as well.

Altering Sequence of Macronutrients

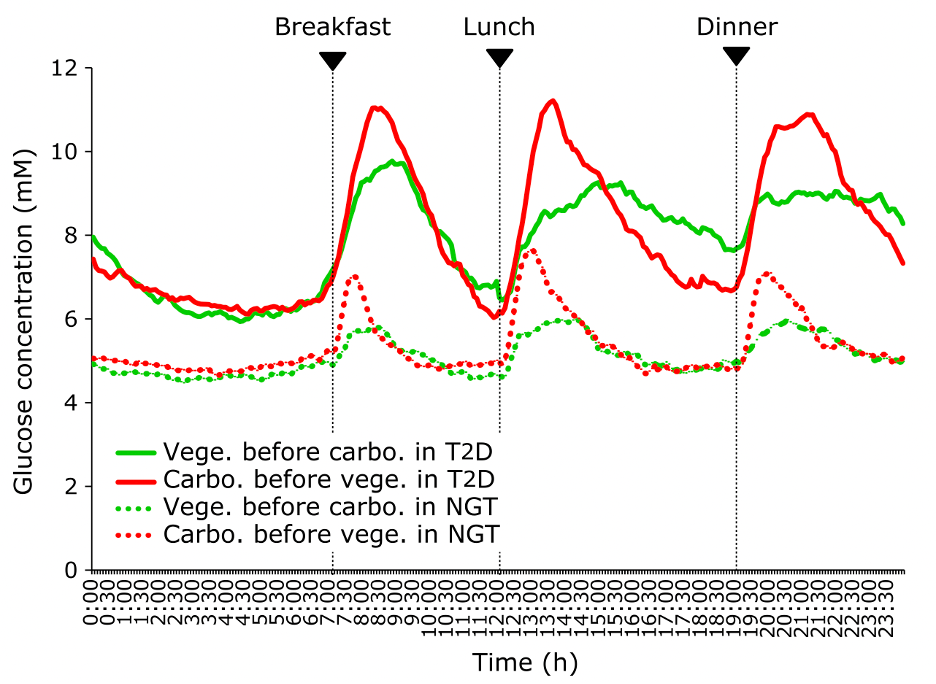

Similar to preloading, altering the sequence of meal components can impact blood sugars. Eating a first course of vegetables or protein before the carbohydrate can lower the postprandial peak and duration following the meal.

This chart from a study in Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition best depicts the general consensus. The solid red line illustrates blood sugar where rice was consumed first, followed by meat and vegetables. The solid green line shows the inverse – veggies and meat first, followed by rice. Results were similar in both T2 and those with ‘normal’ glucose tolerance.

Chrononutrition

Chrononutrition looks at the relationship between nutrients, meal timing, and circadian rhythm. It can also factor in an individual’s chronotype—or the time of day when their body is naturally inclined to sleep. There is some evidence to suggest that increasing the protein and fat content with the evening meal can be a simple strategy to improve postprandial glycemia.

Glycemic Load

Glycemic load takes into account the amount of carbohydrates in a portion of food with it’s glycemic index—or how quickly the food raises blood sugar. The lower the glycemic load, the slower blood sugars will rise after eating.

The glycemic load of a food or meal can be lowered with the addition of fat or soluable fiber, which delays digestion and absorption of carbs. A recent study in the The Journal of Nutrition showed that eating rice alone results in higher postprandial glucose when compared with a mixed meal of rice and lentils.

In Summary

Nutrition modifications to reduce post-meal glucose can be highly effective if used consistently. Mary and Gary also discuss other topics, including insulin timing, injection site care, and physical activity, so I highly recommend watching their webinar to get the full scope of glucose management tools.

You May Also Like

Product Review: Freestyle Libre 3

December 19, 2022

GLP-1 Injectables for Older Adults

April 24, 2024